As you walk down a gravel path through the woods you come upon an idyllic moulin rouge tucked away in a tree-lined gorge. Water from a mill pond gently tumbles over the dam. This is the first impression a new visitor gets when they encounter the Balmoral Grist Mill Museum, located in Balmoral Mills, Nova Scotia. It is easy to focus on the beauty of the scene, and the accompanying inevitable sense of nostalgia. The deeper significance of the site lay in the unseen: a fully preserved example of a 19th century mill that was one of four others that existed on Matheson Brook. Along with the mills there were other businesses, a school and a post office in this once busy little community.

In pre-colonial Nova Scotia, small scale mills were commonplace everywhere water was available. Often, many mills would be supported by one waterway, creating centres of industry and community. So in that sense our mill is not unique, however very few structures survived the decline of the water-powered mill that began in the late 19th century. Ours was very nearly one of them.

As early as the 1880s, there was public lamentation about the disappearance of small community mills. In 1888, Albert Shaw published an article titled “Flour Making in the United States” in the monthly journal, The Chautauquan. It was largely a description of the current state of the industry at the time. Large sections of the article were devoted to looking at the rapid decline of small grist mills similar to our own Balmoral Grist Mill.

Merchant milling on a very large scale is the result of the economies and advantages of the new processes; and the competition of the great mills is causing the abandonment and decay of hundreds of the picturesque, old-fashioned neighborhood mills.… Since 1880 the blighting effect of the great merchant mills upon the small establishments has become visible to everyone.

The decline of small mills in the United States that Shaw referred to in his article was mirrored in Canada.

Between 1891 and 1911 mill numbers in British Columbia dropped by 75%, in Ontario dropped by 47%, in Quebec by 63%, and in the Maritimes by 68%. (Everitt, John and Roberta Kempthorne. Autumn 1993. The Flour Milling Industry in Manitoba since 1870. Manitoba History Vol 26. The Manitoba Historical Society.).

In Nova Scotia’s case there were 398 grist mills in 1851. In 1861 the number had grown to 409. Information compiled from the McAlpine's Nova Scotia Directory of 1907-1908 indicate those numbers had plummeted to less than 50 mills.

Changing patterns of home consumption contributed as well. A study published in 1991 titled A History of Flour Milling in Manitoba addresses this aspect of the decline of small mills:

As dietary needs of his family changed, it became too laborious for a farmer to load his own wheat into a wagon, drive it to town, wait for it to be milled and take it home, considering the decreasing amount needed to feed his family. … Most farmers found it simpler to purchase a bag of mass-produced flour from the large mills.

Along with industrialized flour came industrialized baking. Improved distribution networks, economics of scale and technological advances led to commercial baked goods being more readily available. In 1928, Otto Frederick Rohwedder invented his famous bread slicing machine.

The public loved the convenience of sliced bread and, by 1929; Rohwedder's Mac-Roh Company was feverishly meeting the demand for bread-slicing machines. By the following year, the Continental Baking Company was selling sliced bread under the Wonder Bread label. (National Museum of American History)

The factors that led to small mill decline are well known. But why did some, like the Balmoral Grist Mill survive long enough to be preserved? A History of Flour Milling in Manitoba suggests a possible answer that would apply as well in Nova Scotia:

Surprisingly the Depression brought a temporary halt to this pattern, as rural folk, short of cash but laden with grain they could not sell, exchanged it for flour and livestock feed at whichever local mills had managed to survive. Some communities, such as Virden, even managed to attract new milling enterprises to their communities during this depressed economic period. Mills with relatively modern equipment were then able to take advantage of the increased demand for export flour produced by World War II. (Nicholson, Otto and Ledohowski 1992)

While it’s unlikely the Balmoral Grist Mill contributed to exporting flour during the Second World War, it is conceivable the Mill could have been a valuable local resource during the Depression and in times of wartime shortages at home.

Whatever the circumstances that led to its survival into the 1950s, other mills along Matheson Brook had closed by wartime. Archie MacDonald was the last private owner of the Balmoral Grist Mill and ran it full-time until 1954. By then, the water turbines which powered it had been replaced by a gasoline engine and in addition, a shingle mill had been added as an off-season income supplement.

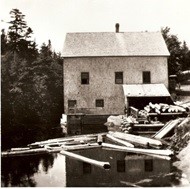

.

Balmoral Grist Mill with shingle mill attached (ca. 1920). Unknown photographer. Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, NS. N-16,962.

Given the overall decline in small scale milling which had begun many decades earlier, it is surprising MacDonald held out for so long.

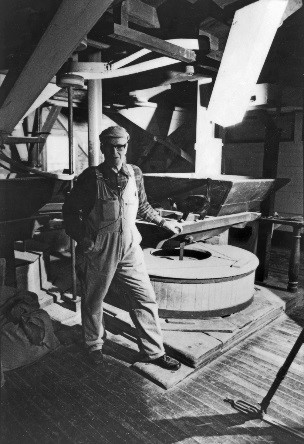

Archie MacDonald (ca. 1974). Unknown photographer. Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax.

Shortly before the Balmoral Grist Mill ceased operation in 1954, the Halifax Chronicle Herald published an article which echoed the 1888 sentiments of Shaw in ‘The Chautauquan’ :

Despite the fact that the mill still turns out a superior product, time and the elements have left their toll on this ancient mill. Because of today’s high speed commercial mills, the Balmoral mills plant is only a convenience for farmers. For Archie E. MacDonald, the present owner and miller, the hours are long and the income small. He keeps the mill in operation because of the historic value of the place. Farmers, too, are concerned over the mill. Since it is almost the last of the old grist mills, they are anxious that it be preserved, but only a co-operative effort by those of government and farmer bodies will keep this last grist mill at Balmoral mills from being the last. Its historical value is beyond question.

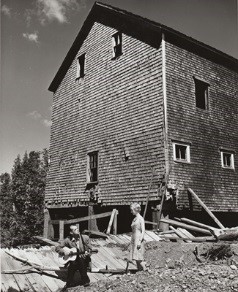

Which brings us to this amazing photo taken in 1964.

Nova Scotia Information Service fonds, "Ed McCurdy at the Old Mill, Tatamagouche" [ca. 1962]. Unknown photographer. Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax, NS. Nova Scotia Archives #17022.

It was a promo shot taken for the Tatamagouche Festival of the Arts (1956-1965) and shows just how close the grist mill came to total ruin.

In 1964 the Sunrise Trail Museum in Tatamagouche acquired the mill. Archie MacDonald returned to operate the mill for them. However, the extent of their renovations was limited by their budget and resources.

In May 1966 the Nova Scotia Government purchased the Balmoral Grist Mill and began an extensive restoration program. An electric motor was installed and the dam was rebuilt. The Balmoral Grist Mill and park were officially opened to the public by Premier G.I. Smith on July 29, 1970.

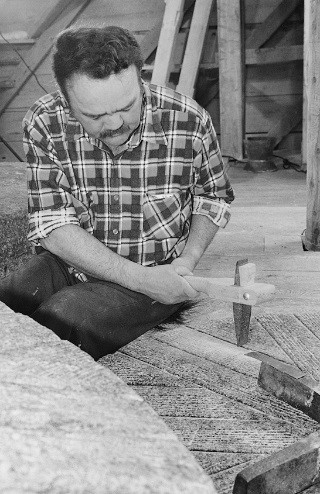

It was about then that John Taylor was hired to become the first miller apprentice.

John Taylor (ca. 1980). Unknown photographer. Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax.

John retired in 2004 but in the interim we’ve had many miller apprentices. Our current miller is Kaleb Fifield who joined us in 2018.

One of the more important and dramatic events in the mill’s history occurred only a few short years ago in 2011 when the old and failing wooden dam was replaced with a modern concrete dam. The project began in August and took almost exactly one year to complete (along with structural reinforcements that had to be made to the mill itself). As dramatic as this project was in and of itself, excitement peaked in October when two record setting rain events washed the cofferdam away exposing the mill to some real peril.

Obviously we survived, but the movement of what had been undisturbed sediment for over a 100 years revealed new information and artifacts that contributed to the story of our mill and some of the others along the brook.

To learn more about that story come and visit us.